Author: May Thu Htet & Myo Min Htun

Anti-corruption has become a national priority (Bak, 2019) of successive governments since the democratic transition in 2011. Since assuming power, the USDP government focused on a clean government and good governance (Saw, 2015), while its successor, the NLD government, on peace and a corruption-free government (Aung, 2017). Under both administrations, there are relevant initiatives in many sectors to tackle corruption that can be defined as “big moments”.

Transparency International (TI) defines corruption as “an abuse of entrusted power for private gain”. Corruption has resulted in inequality, lack of public trust in governments, and negative effects on the economic and political development. Suffering from high levels of corruption in all sectors such as the Judicial system, the Police, the public services, the land administration, the tax administration, the custom administration, public procurement, and in resource sharing (Business Anti-corruption Portal, 2017), Myanmar ranked at the bottom of the TI’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) (Bak, 2019). It was ranked 180 out of the 183 assessed countries in 2011 with a score of 15 on a 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean) scale (Trading Economics, n.d.).

Institutionalization Records of the Governments

The USDP government has made big efforts to curb corruption. Since the inaugural speech of the President U Thein Sein in March 2011, the President initiated a campaign of Good Governance and Clean Government (Bak, 2019). The very first anti-corruption effort was institutionalization of anti-corruption measures. The administration approved an anti-bribery bill in August 2012, ratified the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) on December 20, 2012 (Bak, 2019), and enacted a law for the eradication of corruption in August 2013. Under the 2013 Anti-corruption law, Government officials found to have engaged in bribery can be fined and imprisoned for up to fifteen years, but also have to show their income sources when they are accused of accepting bribes (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, 2013). Former President U Thein Sein also told the government officials in 2014 that gifts worth up to 300,000 kyat (about US$210) are able to be exempt from corruption (Mon, 2014). The law was also established an Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) in February 2014 to investigate claims of corruption, prosecute violations to the 2013 law and produce recommendations to counter corruption (Bak, 2019). It consists of 15 members who are required to declare all of their assets (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, 2013). Five of these members are appointed by the President, five by the lower house, and five by the upper house (Quah, 2016).

In 2014, Myanmar was accepted as a candidate of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), whose goal is to promote good governance of revenues from natural resources and use them for sustainable economic growth and social development, instead of being wasted on short-sighted projects or corrupted (Saw, 2015). Regarding financial corruption, the Central Bank of Myanmar has regulated financial transactions under the 2002 anti-money laundering law and the 2014 money laundering eradication law (Saw, 2015). As a result, the Financial Action Task Force, FATF (an intergovernmental organization combating money laundering) removed Myanmar from its blacklist in June 2016 (Kean, 2018). Acknowledging the importance of the public sector pay, the government also increased several salary increases, raising additional allowances by 30 USD per month in the fiscal year of 2012-13 and raising salaries by 20 USD in 2013-14 (Myanmar Ministry of Finance Budget Department, n.d.). However, regardless of these salary increases, public sector employees still find it difficult to make ends meet as prices increase (inflation in Myanmar ran in excess of 5 percent during these years).

During the campaign period, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi pledged to form a government which is free from corruption for the development of the country as her electoral promise for the 2015 General Elections (Zaw, 2015). Thereupon, there was a remarkable burst of optimism for Myanmar’s future after the NLD winning a landslide victory. Under the NLD administration, Myanmar launched its first report in 2016 that publicly provides data on revenues of the extractive industries. Although the report contains many gaps as it contains little data on the jade industry or the activities of military-linked companies, it can be considered a milestone (World Bank, 2016). In April 2017, the government banned public servants from accepting gifts worth more than MMK 25,000 (US$23) in an effort to stamp out “tea money” incentives (Naing, 2017). The government also amended the anti-corruption law on June 21, 2018. It was the fourth amendment: the first time was exercised under the previous President U Thein Sein’s government on July 13, 2014, and the others on 29 and 31 July, 2016 each under the NLD government. Although the first three did not bring any changes to the law, the fourth amendment covers “any person” misusing their entrusted power, not just “authoritative persons”(Bak, 2019). In the 4th amendment of the Law, corruption is defined as follows:

“The direct or indirect abuse of his position or other means by any person in order to perform an act, refrain from performing a lawful act, [etc.]…such as by giving, receiving, accepting … a benefit from a person…” (Wales, 2018).

The amendment also gave the ACC broader powers to investigate claims and launch preliminary proactive investigations prior to receiving formal complaints. However, the lack of protection for whistle-blowers remains an issue (Bak, 2019). Along with the amendment, the number of complaints also increases up to 10,543 complaints in 2018 from 968 complaints in 2014, 983 complaints in 2015, 710 complaints in 2016, and 2014 complaints in 2017. There are a total of 9,394 complaints in 2019, 478 complaints to Nay Pyi Taw commission office, 528 complaints to Yangon branch office and 388 complaints to Mandalay branch office respectively (Anti-Corruption Commission, 2020).

Legal Actions

The very first anti-corruption action was in January 2013, whereby a former Minister of Communications, Posts and Telegraphs (Saw, 2015), U Thein Tun was forced into resignation. Then, some 17,000 civil servants and about 700 police officers had been punished for corruption in the preceding 20 months up to that year February as a part of a “good governance and clean government” campaign (OECD, 2013). Again in April 2013, a number of senior government officials charged with corruption were forced to retire or transferred away from departments dealing with investment in an effort to root out political and economic corruption (Saw, 2015).

In the name of anti-corruption measures, the ACC filed cases against six officials, including Yangon’s attorney general on the basis of accusations of allegedly dropping charges against three suspected murderers of a comedian in exchange for bribes in September 2018 (Aung, 2018a). The Commission also began investigating the chief minister of the Tanintharyi region, Daw Le Le Maw, in February 2019, on suspicions of awarding contracts without calling for tenders and unclear spending of revenue (Nanda, 2019). ACC also filed charges against three directors of the controversial National Prosperity mining company for having falsely accused civil servants in large mining blocks at “Moehti Moemi” in Mandalay Region’s Yamethin Township of corruption on April 3, 2019 after finding out that the complaint was intentionally made to defame the reputation of the civil servants (Myint, 2019). The biggest case investigated by the ACC so far involves five senior officials of the Directorate of Water Resources and Improvement of River Systems who are alleged to have misappropriated MMK 537 million since 2014. ACC said charges had been filed against the directorate’s director-general U Htun Lwin Oo, adviser and retired deputy director-general U Ko Ko Oo, his successor, U Thaung Lwin, and two directors, U Aung Kyaw Hmu and U Tun Naing Win in its statement on April 10, 2019 (Myint, 2019). Other prominent cases include prosecutions on charges of bribery against: the former director general of the ministry of health and sports (Winn, 2019); a Nay Pyi Taw city official for extracting bribes from traders (Kyaw, 2019); and land registration officials who allegedly accepted payments in return for land transactions and registration (Zaw, 2019).

Corruption Prevention Unit (CPU)

ACC is setting up offices in Yangon and Mandalay. A major initiative currently being implemented by the ACC are the so-called Corruption Prevention Units (CPU) that monitor and report bribery in the line ministries in which they are embedded (Mon, 2018). The units are mandated to refer larger corruption cases in public institutions directly to the ACC for investigation. Later, 14 ministries have formed Corruption Protection Units (CPU), which are Home Affairs Ministry, the Union Government Office Ministry, Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation Ministry, Transport and Communication Ministry, Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation Ministry, Electricity and Energy, Labour, Immigration and Population Ministry, Commerce Ministry, Education Ministry, Health and Sports Ministry, Planning and Finance Ministry, Construction Ministry, Hotels and Tourism Ministry and the Union Attorney-General Office (14 ministries form anti-corruption units, 2019). This could potentially translate into increased capacities to file complaints faster (Aung, 2018b).

As corruption prevention, ACC implements and provides workshops, awareness of anti-corruption, lectures, educational short films, press releases. ACC handed over teaching handbooks titled “Education Programme for Enhancing Honesty” to the Ministry of Education to distribute to primary and middle school teachers around the country (Thant, 2019). ACC conducts several training sessions in ministries, departments, universities, and general administrations offices.

Scores of Anti-corruption Efforts by the Governments

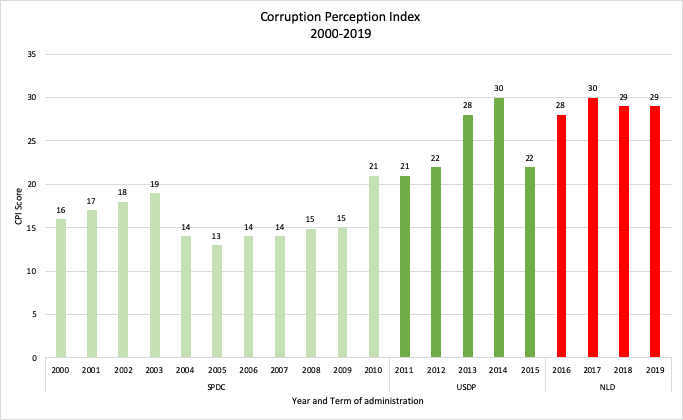

In 2019, the country ranked 130 out of 180 assessed countries and had a score of 29/100. Even though Myanmar is still one of the most corrupt countries in the Asia Pacific region after North Korea, Afghanistan, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Papua New Guinea (Transparency International, 2019), it has improved more than any other countries in the period from 2012 to 2019, increasing its score by 14 points as shown in the following chart.

Source: Dataset from Transparency International

Criticism on Anti-Corruption Law and ACC

The anti-corruption law and the ACC are the primary legal and institutional frameworks for preventing, countering and punishing corruption within the country under the USDP administration (Saw, 2015). But the anti-corruption law was still lacking in eliminating the facilitation payments (Business Anti-corruption Portal, n.d.). The ACC is also not only being criticized due to the fishy past of some of its members who were the former high-ranking military officers (Linn, 2014), and also in question due to the extent to which it can be fully politically independent not only because it has to report to the president and the Hluttaw speakers (Quah, 2016) but also its composition alters together with the elections (Bak, 2019). Some experts also argue that the law is selectively enforced on some persons, for instance, the ACC allegedly investigated only 66 out of the 4,500 allegations of corruption until 2017, while more than 1,000 cases were forwarded to line ministries for internal investigations (Soe, 2018). Importantly, the Commission cannot prosecute the military personnel although they are still civil servants because they are simultaneously governed by military laws and can be tried only in the military courts (Aung & Hammond, 2018). Accordingly, when UNODC conducted the Myanmar First Cycle UNCAC Review in 2016, it reviewed the law needed better provisions for punishing corruption in the private sector and the ACC needed greater political independence and the means to provide some protection for whistle-blowers, as well as concluded that Myanmar needed a number of reforms, including ones that clarify what actually constitutes a bribe (Soe, 2018).

Recommendation

In order to strengthen further anti-corruption actions in Myanmar, the whistle-blower protection bill and public procurement bill should be adopted as soon as possible. Corruption should also be raised awareness not only to the youths but also to the adults through teaching and entertainment. Further recommendations include stricter oversight on the officials’ discretionary powers, increasing salaries of government employees while controlling inflation rate in order to make ends meet, and replacing the direct human interaction with the electronic processing systems (Saw, 2015).

Conclusion

To conclude, corruption remains a significant issue in Myanmar. It has been a national priority of successive governments since the democratic transition. As the legal and institutional improvement, the former USDP government has enacted the anti-corruption law and ACC. It also ratified UNCAC, became a candidate of EITI, and was removed from the black list of FATF. Despite its multiple gaps and strong criticism, the legal and institutional anti-corruption frameworks of Myanmar reflect the will of the government to tackle corruption and are gradually improving. Under the current NLD government, Myanmar launched its first report on extractive revenues industries to the public for the first time. Hence it is noteworthy that anti-corruption efforts inside the country are moving towards the positive side. The government also redefines the acceptance of gifts from those that are worth up to 300,000 MMK to less than MMK 25,000. Amending the anti-corruption law also improves as we can see the fourth one extending to the private sector. Moreover, ACC is setting up CPUs in the 14 ministries. It even attempts to raise awareness of anti-corruption through workshops, lectures, educational short films, and press releases, teaching handbooks, training sessions in ministries, departments, universities, and general administrations offices. Strong political will, a powerful legal framework, effective law enforcement, as well as public cooperation and participation are all crucial elements for a successful anti-corruption campaign. Although investigation in corruption complaints are limited under both administrations, legal actions on a former minister of communication, posts and telegraphs, U Thein Tun under the USDP administration, and on Yangon Attorney General and Daw Lei Lei Maw under the current NLD administration gained public attention and public trust in ACC. Hence all of these relevant initiatives in combating corruption can be interpreted as “big moments” under the USDP and the NLD administrations.

References

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the trustees, board of directors, staff members of Inya Economics or an affiliated organizations/ members with Inya Economics.