TRANSNATIONAL DIGITAL SURVEILLANCE: DIGITAL RIGHTS AND ACADEMIC FREEDOM IN MYANMAR POST-COUP

T. Nandar L.

December, 2024

INTRODUCTION

Myanmar is one of the countries in the world with the most restrictive environments for internet freedom and digital rights. This is the consequence of authoritarian regimes throughout history from severe repression. The rise of digital authoritarianism and shrinking digital spaces are the results of those military coups, particularly worsening after the 2021 incident. These tactics implemented by the State Administration Council (SAC) have a substantial impact on the country’s intellectual discourse and academic freedom (Freedom House, 2023). The surveillance systems including the controversial Electronic Identification (e-ID) system function as a significant tool for monitoring and controlling citizens’ movements (Civic Media Observatory, 2024). This further enables a form of transnational repression, which occurs when a state’s control transcends beyond borders (Techagaisiyavanit et al., 2023), targeting political and academic dissent, particularly among resident and exiled scholars (including students, academics, and activists). Thereby, it poses a substantial challenge to intellectual discourse within the country. The interconnected mechanisms of repression severely limit academic freedom, which is a fundamental right that allows scholars and researchers to pursue knowledge without the fear of censorship or retaliation (Marceta, 2023). As a result, the impact mechanism named ‘self-censorship’ is on the rise in Myanmar’s academic communities, most notably confined to discussions on economics, politics, and social affairs of the country (Justice For Myanmar, 2024; Cimphony, 2024). The transnational control mechanisms that surround the countries add to the complex situation by piling on top of digitally enabled authoritarian practices. Therefore, this blog tries to discuss the authoritarianism control via digital and transnational surveillance, its threats to academic freedom in Myanmar and urges the need for international solidarity and protective measures for scholars at risk.

DIGITAL SURVEILLANCE TACTICS AND IMPACT ON ACADEMIC FREEDOM

Since the introduction of internet connectivity in 2000, digital surveillance has become deeply entrenched in Myanmar, marked by significant restrictions within the military-controlled telecommunications sector. A period of brief liberalization followed the reforms initiated in 2011; however, the military regime has since exploited advanced surveillance technology to monitor citizens more rigorously (Justice For Myanmar, 2024). These tactics can be traced back through various political upheavals in history: the 1962 coup led by General Ne Win, the subsequent military rule established in the aftermath of 1988, and the latest coup in 2021 led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. The nature of digital repression follows similar trends that have evolved throughout the decades from the initial restriction of using the internet to the increased measures taken after 2021.

These include social media monitoring to suppress dissent, the introduction of facial recognition technology as part of the junta’s “Safe City” initiative—which poses a significant threat to individual privacy and freedom of expression—and frequent internet shutdowns designed to control information flow during civil unrest (Human Rights Watch, 2021; Freedom House, 2021; Access Now, 2023; Khine, 2023). The motives of digital authoritarianism tend to take place most heavily on social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter (Wilson, 2022), and Telegram. The report from Freedom House (2023) reveals that Myanmar ranks as the second most repressive country in terms of internet freedom, highlighting how certain Telegram channels have been employed to distribute pro-military propaganda while identifying and doxing (unauthorized sharing of personal data online) members of the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM). Consequently, scholars, activists, and journalists face threats that deter them from addressing politically sensitive subjects, exacerbating data gaps within the academic community (Schlumberger et al., 2023).

In authoritarian contexts like Myanmar, academic freedom is crucial for challenging oppressive regimes and mitigating human rights violations. However, the pervasive atmosphere of fear fostered by digital surveillance contributes to a widespread ‘chilling effect’ within academia, stifling individual expression and undermining the integrity of academic research. Scholars increasingly refrain from engaging with politically sensitive topics to avoid unwanted attention from pro-military groups or authorities, driven by fears of reprisal. This self-censorship compromises the quality and integrity of academic output, significantly limiting scholarly pursuits (OHCHR, 2022; Cimphony, 2024; Grove, 2024).

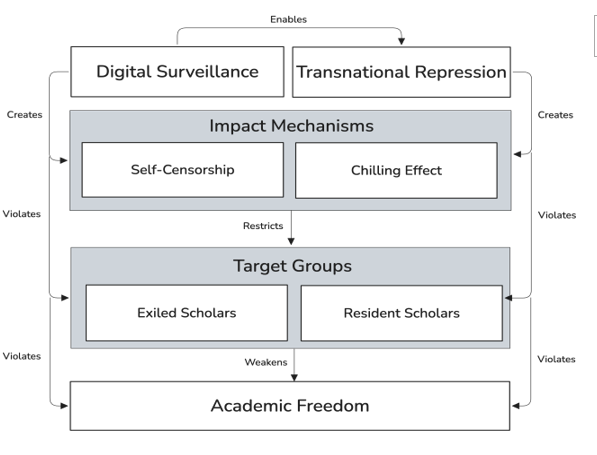

Figure 1: Conceptualizing the Impact of Digital Surveillance on Academic Freedom

Figure 1 illustrates how digital surveillance and transnational repression work collaboratively to systematically threaten academic freedom for scholars both within and outside of Myanmar, particularly in the post-coup era. The two enablers—digital surveillance and transnational repression—interconnect to deprive academic freedom through both direct and indirect means. Such a dynamic fosters two major impact mechanisms: chilling effect and self-censorship. These mechanisms make academic activities systematically constrained for both exiled and resident scholars which undermines academic freedom in various ways. The consequences ultimately create significant challenges for them in pursuing academic endeavors and disseminating knowledge freely, regardless of their geographic location.

According to a report from Data For Myanmar (2023), between February 2022 and September 2023, there were 1,316 documented cases of actions taken against individuals being engaged in anti-military movements online across social media platforms, Facebook, TikTok, and Telegram as aforementioned. Notably, from May to August 2022, more than 100 people were arrested monthly, while 500 detainees were recorded within four months, predominantly from urban areas such as Mandalay and Yangon. Individuals engaged in political expression and human rights activism face severe threats under the junta rule, especially, if they are affiliated with any opposition groups. For example, Dr. Akar Moe Thu, a professor at Yangon University, received a three-year prison sentence under Section 505(a) of the Penal Code for leading an anti-military protest (The Irrawaddy, 2022).

Reports by Engage Media (2013) reveal that individuals’ phones are searched for evidence of protests, political discussions, or critical posts at security checkpoints. This scrutiny is compounded by the crackdowns on VPNs, travel restrictions, and targeted repression in areas such as Sagaing, Kachin, and Rakhine. Such breaching of fundamental rights ultimately leads to arbitrary arrests (Khonumthung News, 2022; Aung, 2023; Kamaryut Information Scout Channel, 2023). Another form of repression fuelling the chilling effect is targeting on individuals who are affiliated with opposition organizations. For example, the case of the president of Parami University, Dr. Kyaw Moe Tun, who is a fellow of the Open Society University Network’s Threatened Scholars Integration Initiative (OSUN-TSI). He was charged with incitement under Section 505 (a) and sentenced to three years in prison following 11 months in detention (OSUN, 2023).

Similar cases, such as those involving ‘Kaung For You,’ in which the data of teachers and students suspected of NUG (National Unity Government) affiliation were exposed, and the Bright Future Federal School (BFFS), where military forces detained some teachers and students due to their affiliations, further highlight a repressive environment (Thit, 2022; The Irrawaddy, 2023). On the other hand, there is alarmingly little protection from a legal standpoint. For example, on January 25, 2022, the SAC issued a statement discouraging the use of social media and other online platforms for promoting anti-military movements and warned of potential legal actions under several laws, including Section 33(a) of the Electronic Communications Act and Sections 124A and 505-A of the Penal Code. The military-controlled news outlets frequently report such actions. This reflects clear violations of digital rights including accessing personal data without consent and suppressing voices without judicial oversight (OHCHR, 2022; Khine, 2023).

Private sectors, including telecommunications and banking, are similarly influenced by the military regime, contributing to digital surveillance repression, which serves as an additional tool in the junta’s censorship mechanism. According to the reports from Radio Free Asia, 700 mobile payment accounts were closed in May 2023 alone (Access Now, 2024). Moreover, the SAC formed a committee under Order No. 246/2023 that aims to limit the proliferation of various online content including hate speech, fake news, pornography, and political criticism in collaboration with telecommunications companies (Printing and Publishing Department, 2024). These actions further exemplify the military’s blatant violations of freedom of expression and human rights.

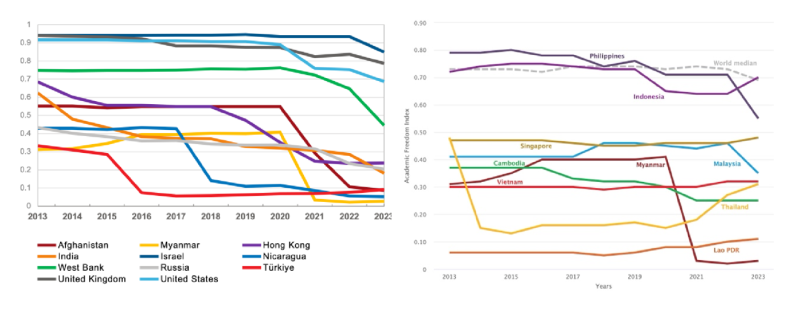

Source: Free to Think Report, Scholars At Risk, 2024 & V-Dem Core, World Bank Group, 2024

The reports from Scholars at Risk (2023) and the Academic Freedom Index (World Bank Group, 2024) reveal a significant decline in academic freedom globally, with Myanmar ranking among the countries experiencing the most severe deterioration. Figure 2 illustrates a concerning trend over the past decade, as more than 22 countries, representing half of the world’s population, have experienced a decline in academic freedom. This trend highlights growing challenges to intellectual discourse and the free exchange of ideas on a global scale. Under this circumstance, Myanmar became one of the five countries with the worst conditions for its academic freedom, alongside China, Iran, Nicaragua, and Turkey, and notably the worst within the ASEAN region (The Association of Southeast Asia Nations). Indeed, things have become even worse after the 2021 coup, since those individuals and organizations who opposed the military regime faced arrests, severe sentences, and enforced shutdowns of operations, particularly the students, scholars, journalists, and activists.

The concept of transnational repression enables the multifaceted phenomenon of digital surveillance across national borders by extending state control into diaspora communities or political exiles. Techagaisiyavanit et al. (2023) state that the issue is a critical dimension of spatial encroachment, where home states make use of available digital technologies to keep track of and intimidate individuals living abroad. Exiles’ vulnerability is magnified by the policy gaps of host states and their lack of adequate digital security measures, which accidentally help facilitate transnational surveillance mechanisms. In examining the ASEAN’s regional security landscape, patterns of digital repression can be seen in each nation employing unique yet interconnected strategies. For instance, Thailand’s lèse-majesté laws (Manushya Foundation, 2023), Cambodia’s “National Internet Gateway” (Scholars at Risk, 2022), and Singapore’s POFMA Act (Amnesty International, 2021; Freedom House, 2023) reflect systematic approaches to constraining academic freedom. Meanwhile, in Indonesia and the Philippines, human rights researchers face harassment and digital surveillance (Scholars at Risk, 2022; Human Rights Watch, 2022; Amnesty International, 2022). Malaysia restricts digital spaces through web and social media monitoring (Access Now, 2021; ARTICLE 19, 2023), while Laos maintains stringent internet controls that severely limit scholarly discourse (Freedom House, 2021; Civil Rights Defenders, 2021). These coordinated efforts create a chilling environment that fundamentally threatens freedom of expression and movement, including academic freedom, open dialogue, and critical scholarly activities across the region.

The systematic nature of digital repression in ASEAN countries indicates a broader pattern of transnational surveillance that transcends traditional geographic boundaries, utilizing technological capabilities to suppress academic and political dissent. Surveillance mechanisms oppress scholars in their home country, while migration itself is heavily loaded with lots of administration and financial struggles. Take from the example of the case of Ma Myat Ei Ei Phyo (Duncan, 2021). Thailand is particularly a critical case study for understanding transnational repression as the country has enabled repression against dissidents from various countries, including Myanmar. Human Rights Watch documented the numerous cases where the country has facilitated surveillance, violence, and enforced disappearances of activists seeking refuge in Thailand, undermining the country’s historic role as a haven for those fleeing persecution (RFA, 2024; Human Rights Watch, 2023).

In November 2024, the military junta accused the Mandalay Medical University of issuing fake medical certificates affiliated with the NUG. The citizens were arrested for offering the notary service of those certificates for those students’ university admissions in Thailand. Nevertheless, the university later recognized those certificates as legitimate (Connect Burma, 2024). Therefore, the fear of this retaliatory action against colleagues or family members has become a key driver of anxiety, compounding the mental health struggles of those affected (Open Briefing, 2024). The absence of robust legislative frameworks to protect scholars and political exiles raises significant concerns combined with the vulnerabilities faced by individuals escaping repressive regimes (Techagaisiyavanit et al., 2023).

Academic freedom in Myanmar continues to face substantial threats due to the convergence of digital surveillance and authoritarianism. The military regime’s deployment of advanced surveillance technologies, including internet shutdowns, social media monitoring, and biometric data collection, creates a climate of pervasive fear. The resultant chilling effects and self-censorship have transformed into a survival strategy for scholars, limiting intellectual discussions and hindering research outputs, which fundamentally undermines the core principles of the academic community. In fact, Myanmar exemplifies how digital authoritarianism undermines academic freedom, threatening the integrity of intellectual discourse and the fundamental rights of scholars. As the repression accelerates, the international academic community must prioritize the protection of academic freedom and digital rights in Myanmar, advocating for the safeguarding of scholars and facilitating the creation of safe spaces for dialogue and intellectual exchange.

The global academic community, human rights organizations, policymakers and practitioners need to unite in solidarity to amplify the voices of those overshadowed by digital authoritarianism. In fact, there are several human rights and humanitarian organizations (including the UN Human Rights Council (HRC 47), Article19, Manushya Foundation, Scholars at Risk, Access Now., etc.) dedicated to supporting individuals facing risks from digital authoritarianism. This blog, therefore, reiterates the following key advocacy initiatives and strategies in brief that require critical attention to address urgent actions and strengthen vital measures.

With these initiatives and measures, the global academic community can play a significant role in safeguarding academic freedom and digital rights in Myanmar and beyond the regions with similar challenges. This is the fight for not just a mere local issue, yet it transcends borders representing a collective movement for democracy and the protection of human dignity. Indeed, this issue extends beyond academic freedom per se; it is a fundamental defense of the human right to think freely, ask critical questions, and evolve without fear. As a matter of fact, upholding these freedoms in Myanmar and beyond the region involves moral obligation and strategic imperative for the advancement of global intellectual and democratic progress.

References

Access Now. (2023). Digital rights are human rights: Holding Australia, Georgia, Myanmar, and Nauru to account at the U.N. https://www.accessnow.org/digital-rights-are-human-rights-holding-australia-georgia-myanmar-and-nauru-to-account-at-the-u-n/

Access Now. (2024, January 31). A call for global solidarity and decisive action to end Myanmar’s military rule and ensure victory for the people resisting dictatorship PUBLISHED: 31 January 2024. Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/press-release/statement-myanmar-coup-en/

ARTICLE 19. (2023, July 6). UN: Myanmar junta tightens its grasp on online spaces. https://www.article19.org/resources/un-myanmar-junta-tightens-its-grasp-online-spaces/

Aung, M. M. (2023, June 2). ကျုံပျော်မြို့ရှိ စစ်ကောင်စီဂိတ်များတွင် အမျိုးသားများ၏ ဝတ်စားဆင်ယင်ပုံကို ကြည့်၍ တင်းတင်း ကျပ်ကျပ် စစ်ဆေးမှုများပြုလုပ်. Ayeyarwaddy News. https://ayartimes.com/?p=19939

Cimphony. (2024). Myanmar’s digital repression 2024: Censorship, surveillance, shutdowns. https://www.cimphony.ai/insights/myanmars-digital-repression-2024-censorship-surveillance-shutdowns

Civic Media Observatory. (2024, March 13). Undertones: Myanmar’s e-ID system means progress or surveillance? Global Voices. https://globalvoices-org.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/globalvoices.org/2024/03/12/myanmars-e-id-system-progress-or-surveillance/amp/#amp-wp-footer

Connect Burma. (2024, November 23). စစ်ကောင်စီက တစ်ဖက်သတ် Black List ကြေညာထားတဲ့ကျောင်းသူနှစ်ဦး ချူလာ မှာ ကျောင်းတက်ခွင့်ရ. Connect Burma – Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=1034095018731904&id=100063942466377&rdid=lelAS55kmZ2XRmU5

Data For Myanmar. (2023, October 8). People detained for criticizing the junta and supporting the opposition forces online. https://www.datawrapper.de/_/417jF/

Duncan, K. (2021, September 7). “I was really desperate”: Myanmar’s student exodus amidst military coup. Southeast Asia Globe. https://southeastasiaglobe.com/myanmars-student-exodus/

Eleven Media. (2024, November 24). Fake medical certificates issued by NUG-linked institution lead to arrests. Eleven Media Group. https://elevenmyanmar.com/news/fake-medical-certificates-issued-by-nug-linked-institution-lead-to-arrests#:~:text=Authorities%20have%20arrested%20three%20individuals,to%20Chulalongkorn%20University%20in%20Thailand.

Engage Media. (2024, January 15). The Dangers of Checkpoints: Stories of arrest and censorship from Myanmar civilians. Engage Media. https://engagemedia.org/2024/youth-myanmar-checkpoints/

Freedom House. (2021). Freedom on the Net 2021: The global drive to control big tech. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/FOTN_2021_Complete_Booklet_09162021_FINAL_UPDATED.pdf

Freedom House. (2023). The repressive power of artificial intelligence. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2023/repressive-power-artificial-intelligence#the-repressive-power-of-artificial-intelligence

Grove. (2024, May 7). Digital surveillance of scholars ‘eroding academic freedom.’ Times Higher Education (THE). https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/digital-surveillance-scholars-eroding-academic-freedom

Human Rights Watch. (2021). Myanmar: Facial recognition system threatens rights. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/12/myanmar-facial-recognition-system-threatens-rights

Human Rights Watch. (2023, April 12). Thailand: Myanmar Activists Forcibly Returned: Thai Government Aids Junta’s Persecution of Opposition. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/04/12/thailand-myanmar-activists-forcibly-returned

Justice For Myanmar. (2024, June 19). The Myanmar junta’s partners in digital surveillance and censorship. https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/stories/the-myanmar-juntas-partners-in-digital-surveillance-and-censorship

Kamaryut Information Scout Channel – KISC. (2023, August 8). ကမာရွတ်မြို့နယ်အတွင်းရှိ အကြမ်းဖက်စစ်ကောင်စီနှင့် အပေါင်းအပါများ၏ လှုပ်ရှားမှုများ. Kamaryut Information. https://t.me/KMYINFO/2825

Khine. N. K. (2023). Digital rights in post-coup Myanmar: Enabling factors for digital authoritarianism. https://www.academia.edu/download/110352314/document_1_.pdf

Khonumthung News. (2022, February 24). Regime Cracks Down On VPNs In Hakha. Burmese News International. https://www.bnionline.net/en/news/regime-cracks-down-vpns-hakha

Manushya Foundation. (2023). ACSCAPF23 joint statement. https://www.manushyafoundation.org

Marceta. (2023). The definition, extent, and justification of academic freedom. https://www.pdcnet.org/ijap/content/ijap_2023_0999_7_10_185

OHCHR. (2022, June 7). Myanmar: UN experts condemn military’s “digital dictatorship.” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner – OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/06/myanmar-un-experts-condemn-militarys-digital-dictatorship

Open Briefing. (2024, October 10). Healing invisible scars: Supporting the mental health of Myanmar’s exiled activists. Open Briefing. https://www.openbriefing.org/blog/supporting-the-mental-health-of-myanmars-exiled-activists/

Open Society University Network. (2023, November 14). Threatened Scholars: Kyaw Moe Tun on Outrunning a Coup While Building a Liberal Arts University for Burmese Students. OSUN News. https://opensocietyuniversitynetwork.org/newsroom/threatened-scholars-kyaw-moe-tun-on-outrunning-a-coup-and-building-a-liberal-arts-university-in-myanmar-2023-10-20

Perplexity AI. (2024). Acknowledgment of utilizing Perplexity writing assistant. From https://www.perplexity.ai

Printing and Publishing Department. (2024, January 31). ပြည်ထောင်စုသမ္မတမြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်ပြန်တမ်း မှတ်ပုံတင်အမှတ်–၃၉ [Press release]. https://www.moi.gov.mm/ppd/book/2360

RFA & Benar News. (2024, May 15). Thailand assists neighbors in repressing dissidents: rights group. Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/cambodia/hrw-thailand-05152024212114.html

Schlumberger, O., Edel, M., Maati, A., & Saglam, K. (2023, July 3). How authoritarianism transforms: A framework for the study of digital dictatorship. Government and Opposition, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2023.20

Scholars at Risk. (2023). Free to think 2023: Report of the Scholars At Risk Academic Freedom Monitoring Project. https://www.scholarsatrisk.org/resources/free-to-think-2023/

Techagaisiyavanit, W., Chokprajakchat, S., & Mulaphong, D. (2023). RETERRITORIALIZING THAILAND’S TRANSNATIONAL SPACE? World Affairs, 186(3), 717–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/00438200231176821

The Irrawaddy. (2022, January 20). Myanmar Professor Jailed for Three Years for Leading Anti-Coup Protest. The Irrawaddy. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-professor-jailed-for-three-years-for-leading-anti-coup-protest.html

The Irrawaddy. (2023, August 8). NUG ကျောင်းတွင် ပညာသင်ကြားသဖြင့် အဖမ်းခံရသူများ ပြန်မလွတ်သေး. The Irrawaddy. https://burma.irrawaddy.com/news/2023/08/08/372338.html

Thit, H. (2022, July 21). At least 30 teachers detained following data leak and arrest of NUG-linked school founder. Myanmar Now. https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/at-least-30-teachers-detained-following-data-leak-and-arrest-of-nug-linked-school-founder/

Wilson, R.A. (2022, November). Digital authoritarianism and the global assault on human rights. Human Rights Quarterly, 44(4), 704–739. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2022.0043

World Bank Group. (2024, March 26). V-Dem Core Database. World Bank Group | Prosperity Data360. https://prosperitydata360.worldbank.org/en/dataset/VDEM+CORE